Professor

Shadows on the Wall

The study of art history is usually conducted through photographs of objects projected on the wall of a dark classroom. While not advisable, it is possible to earn a Bachelor’s degree in art history without ever seeing an actual work of art; never leaving Plato’s cave. Although the quality and accessability of digital imagery makes the best of a less-than-ideal teaching scenario, one must face the humbling reality that much of the work of a professor of art history is to talk about illuminated images as if they were somehow the objects they represent, not just a shadow of them. (I cannot help but think of work of William Kentridge—below—in this context.)

Although some courses are, by the nature of their material, consigned to words and reproductions, a campus museum can offer a much needed dose of reality. Thus, one path out of the cave and to reality is through seminars built upon the resources of a campus collection, where the objects serve as a…

point of inspiration;

basis for a hypothesis;

focus of research, analysis, interpretation;

piece of evidence in an argument; and

means to shaping knowledge.

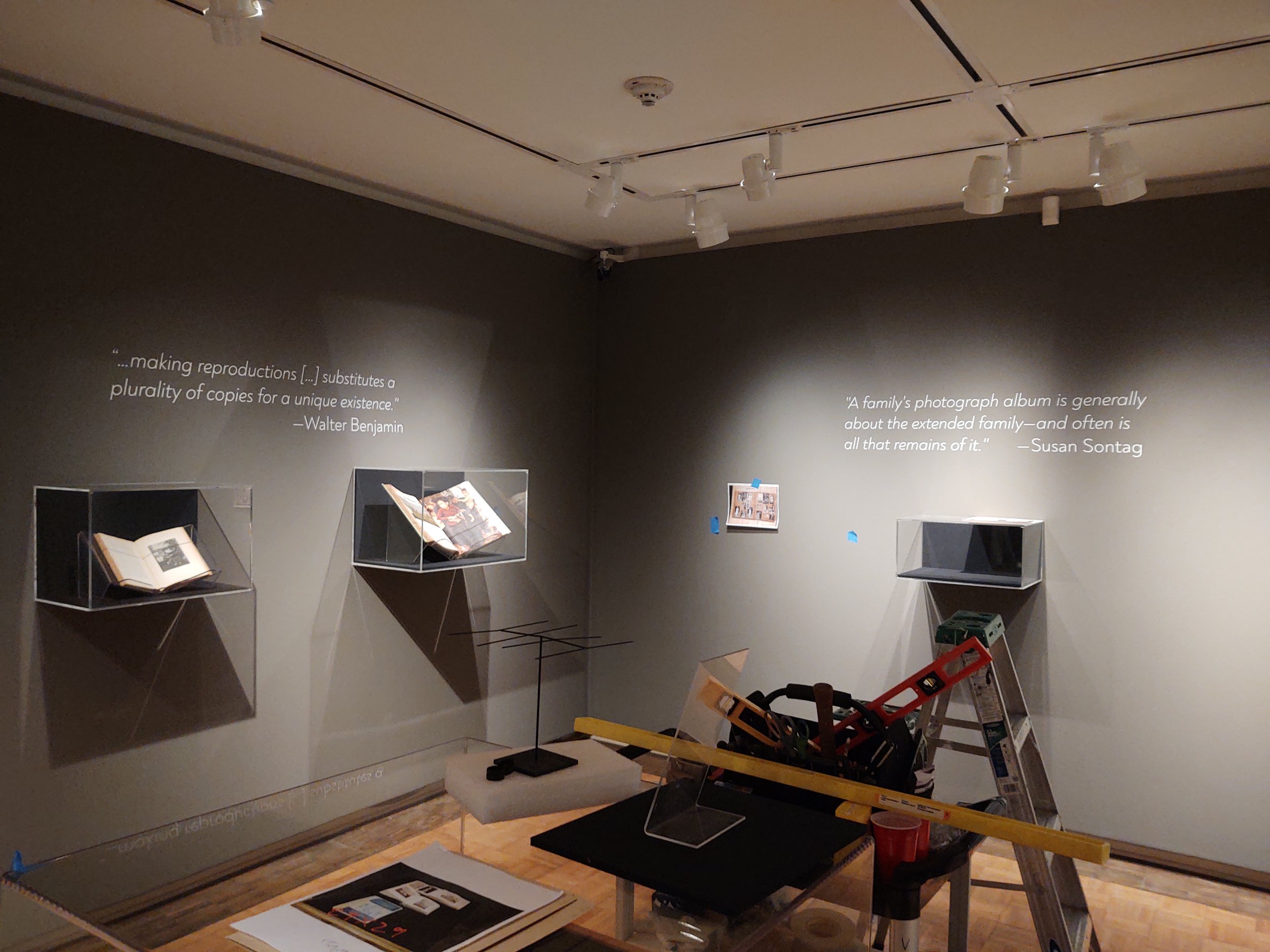

I have led several such seminars and independent studies projects for as few as one or two students to as many as a dozen. Typically, such projects span two semesters. The first semester concentrates on exhibition concept development, research, and writing; the second semester is devoted to exhibition design, object preparation, and catalogue/didactic production. This is the type of course that fully emerges students in the physical and intellectual aspects of objects.

Case Study

In Light of the Past: Experiencing Photography 1839–2021

For this exhibition, I posed a question to the six students enrolled in my exhibition seminar. How do we experience photographs? It wasn’t an entirely fair question on my part, since it was based on the knowledge that all of the students in the seminar were born in 1997, and their experience of photography was through digital camera phones. The object of the project would be retrospective in nature, for them to consider the variety of ways photographs were experienced in the pre-digital era.

Exhibition Catalogue

Laying out photographs for mounting

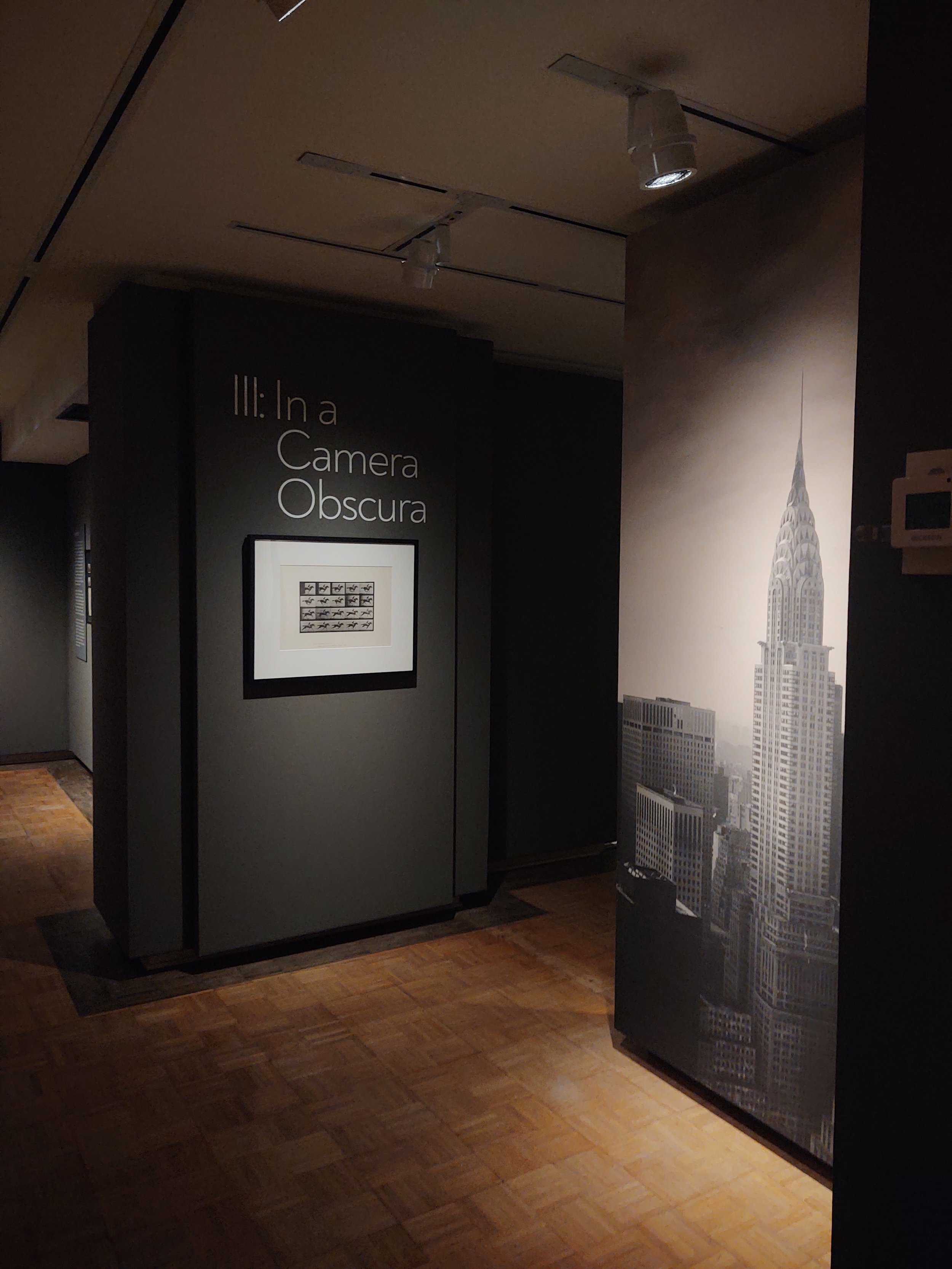

Installation

Entrance gallery dedicated to photography as art

Ambrotypes, Ferrotypes, Carte de visites

Mounted albumen photographs

Entrance to Projecting Gallery

After a series of introductory sessions, where we reviewed various types of photographs in the collection, each of the students were to identify and research one major type and how they would have been experienced by viewers. Their research would result in a scholarly essay that formed one of the six themes of the exhibition and its catalogue. The themes centered on the following photographic types: daguerreotypes, cabinet cards, art photography, snapshots, photo-journalism, and projections. This (overly) ambitious project featured 132 objects and a 142-page color catalogue.

Such intensive study of objects in hand, from a range of perspectives, leaves a deep impression on students, one that takes them well out of the dark classrooms and into the light of curatorial work, where one works day-to-day with real material, not a shadow thereof.